- Home

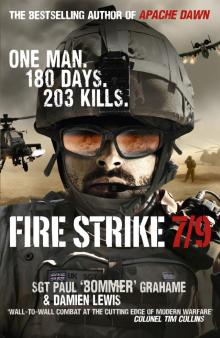

- Paul Grahame Bommer

Fire Strike 7/9 Page 17

Fire Strike 7/9 Read online

Page 17

Almost immediately, a beast of a Mastiff armoured vehicle hit a mine. It had a shredded tyre, but that was about the only damage. I called the same Chinook back in again, and this time it lifted off with one of the lads from the Mastiff. The injured lad had been knocked off his perch by the shockwave of the explosion, and broken some ribs.

It was 1900 hours by the time we reached FOB Price. This was where I was getting off. I told the packet commander I’d listen in on the radio during their drive to Camp Bastion. It was a well secure patch of road, the air would remain over the convoy, and I’d direct any controls if need be. An hour later the convoy was safely back at base.

It was a joy to be reunited with my FST. Well, kind of. Chris, Sticky and Throp gave me a good ribbing about my ‘little prick’. Once we’d got that out of the way, we got down to business. We were leaving FOB Price first thing the following morning and heading out to the Green Zone.

We were making for three new bases at Rahim Kalay and Adin Zai. Patrol Base Sandford — named after Sandy — had been established on the ridge line overlooking the jungle. To the east lay Monkey One Echo, a second fortified compound set at the limit of our eastward push into enemy terrain. But the real jewel in the crown was Alpha Xray, set right in the heart of the Green Zone, on the verges of the Helmand River.

Together, the three bases formed ‘the Triangle’, an area in which we were to find, fix and kill the enemy. The Triangle served as a chokepoint, restricting the flow of men and weapons throughout the length and breadth of the Green Zone. As such, it was the front line between our big garrisons at Gereshk and all stations south, and the enemy.

We were going in to hold that front line for anything from two weeks to the entire remainder of our tour. Get in. I had one crucial thing to do before packing all my gear and getting some kip. I had to ring my dad and wish him a happy birthday.

As I dialled the number, I reflected on how the two of us had parted on not the best of terms. I hoped he was over it, for I didn’t want any rifts in the family. A few days before leaving for Afghanistan, I’d called to have a chat with him. We were close, and I didn’t do much in life without talking to him about it first. At first my dad had never believed I’d make it in the Army, but that was well behind us now. He understood that the Army was my life, and he was proud of what I was doing. In passing, I mentioned I’d just taken out some extra life insurance for the wife.

‘Why’re you doing that?’ he asked. ‘The Army provides life insurance, don’t they?’

‘Yeah, I was just getting some extra. A top-up, like.’

‘But why’re you doing that?’ he asked again.

‘Well, just to make sure she’s OK. She’d have the mortgage paid off and a big lump sum, so she’d be all right in life.’

‘But why’re you doing that?’ my dad asked for a third time.

‘What d’you mean — why am I doing that?’

‘You’re just wasting your money, aren’t you?’

‘No. Not if owt happens.’

‘What’s going to happen?’

‘Dad, I’m going to Afghanistan.’

‘What d’you mean by that?’ he asked.

‘I mean it’s Afghanistan, and bad things happen in Afghanistan.’

My dad was worried, but I told him and my mum that soldiering was my job, and that I had to go. I hoped, with a happy birthday phone call from Helmand, I could put all of that to rights. Sure enough, Dad was over the moon to hear from me. The life insurance thing wasn’t mentioned. I guess he’d reconciled himself to the fact that his son had chosen to go into harm’s way to get a job done.

There was no way we could let a bunch of medieval lunatics like the Taliban take over an entire country, less still to use it as a base for global terrorism. That was what we were fighting to prevent. The hard-line Taliban hate our way of life. They want the world to be like Afghanistan under their rule. The Afghan people deserve more. We all do. I’d fight to the last man to prevent my family and my fellow countrymen ending up in a world like that. My dad hated me risking my life, but at the same time he understood what I was doing.

Sticky, Throp, Chris and I joined a resupply convoy heading out to the Triangle. We arrived at PB Sandford at night, after a hard day’s driving through hostile terrain. We’d made painfully slow progress, as we checked for IEDs and ambushes all the way. Upon reaching the darkened base, Butsy told us we’d have our first briefing after stand-to.

And I felt like I was home again.

Fifteen

THE KILLING BOX

The only change about Major Butt since I’d last seen him was his weeks-old stubble, and he was noticeably thinner. The well at PB Sandford was infested with bloodworms, and bottled water was too precious to waste shaving. By default, battle dress in the Triangle was going to be big beards all around. In his usual, gruff manner, the OC got down to business.

Butsy indicated a section of terrain on the map that he’d spread before us. ‘Lads: we kept mowing the grass, and it kept growing back again. We’d push the enemy out of here, and they’d creep right back in. So, now we’ve pushed the enemy out once and for all. The feature we can easily recognise as our front line is the Adin Zai road. That’s here.’

The major traced a thin line on the map snaking through the Green Zone.

‘The operational concept behind our bases is as follows.’ The OC glanced in my direction. ‘Since you were last here, we pushed out from Rahim Kalay and took the Triangle. We pushed out of Rahim Kalay, using a double hook: B Company in the north, and soldiers from the Afghan National Army in the south. We hit massive resistance, and it was there that we lost Guardsman Hickey.’

The OC paused. ‘The ANA lads did well, and were supposed to remain with us. Unfortunately, they were pulled away. So whereas it was supposed to be two companies holding the Triangle, we are now one. I’ve had to work out how best to use B Company to dominate the area. Our brief is to hold the terrain, and block the enemy out of Rahim Kalay and Adin Zai, enabling reconstruction and security in the areas we’ve secured.

‘We have four platoons: one at Alpha Xray, one at Monkey One Echo and a platoon-plus here at PB Sanford. The platoons are on four-day rotations around the bases. In any of the three we are effectively surrounded. We’ve been taking hits just about every night, and at times we’ve been under threat of being overrun — especially down at Alpha Xray. I’m going to start using good old fighting patrols at night, to keep the enemy on their toes. We have to take the initiative, and the battle, to the enemy.

‘FST ops are unchanged,’ the OC continued. ‘You’re to use the air, guns and mortars in support of the lads, to smash the enemy. We faced fierce resistance getting in here, and we’ve been very busy since. You will have your hands full. It’s the same-old same-old.’ He glanced up and gave us his tough smile. ‘And Bommer — you’re to do whatever you want with the air to look after the lads here in the Triangle.’

‘Yes, sir.’ I was back in action as B Company’s JTAC.

I was on a steep learning curve. Before leaving FOB Price Damo Martin had got me into the Fire Planning Cell (FPC) tent and handed me a bundle of new maps. The GeoCell had done a sterling job of compiling mapping that could be passed to the pilots on disk, and uploaded on to their weapons computers. The same maps were provided to us JTACs.

Most importantly, those maps had just about every known enemy position marked on them, with a codename. Enemy positions in the Triangle had been given the Golf Bravo prefix. So, for example, a tree-line might be Golf Bravo Nine Three. In theory, all I needed to do to talk the air on to target was give the pilot the GeoCell codename. It was a great concept: I wondered how it would it work in practice.

As I glanced over the OC’s maps, the strategy behind the three bases in the Triangle began to make sense. Alpha Xray was a simple, mud-walled compound reinforced by rolls of razor wire, and with sandbagged rooftop positions. It was located in the heart of Adin Zai — in what had recently been prime enemy te

rritory. It was the bait to lure them out to fight us.

PB Sandford was set a kilometre back from Alpha Xray, on the ridge line. It was a large compound, with thick mud-brick walls reinforced by HESCO barriers. From the base, the platoons had eyes on the Green Zone rolling out below, including Alpha Xray (AX). AX was linked to PB Sandford by two small dirt tracks that snaked their way through the bush, enabling convoys to fight their way through and resupply the base.

Monkey One Echo was 800 metres due east of PB Sandford, and set on the lip of the high ground. It was thrust against the limit of known enemy territory, and was our second provocation. The thick bush of the Green Zone ran right up to the walls, so it was almost as vulnerable as Alpha Xray. From Monkey One Echo a huge swathe of enemy terrain was visible, and the base was linked to PB Sandford by a dirt track, enabling resupply. The three bases formed a kill-box, in which to trap and smash the enemy.

After Butsy’s brief we moved down to Monkey One Echo (MOE), our home for the coming days. MOE was another, massive compound with thick mud-walls. It was owned by a wizened Afghan elder who refused to be cowed by the Taliban.

Trouble was, we weren’t to go inside the compound. We knew if we did the Taliban would really start to target the old boy’s family. Instead, the lads had made a camp against the outside back wall. That wall was high enough to provide cover for our Vector. With a camo-netting lean-to slung against it, at least there was some shade. The more fortunate lads had US Army camp beds — a fold-out aluminium frame with canvas covering. Those like me without dossed down on the dirt.

From the vantage point on top of the compound wall the view over the old boy’s compound was spectacular. In the foreground there were the dome-roofed buildings of his family home, complete with a sculpted mud arch like a half-doughnut. That arch led into a massive, three-storey square tower, with spyholes. It looked like something out of The Arabian Nights, and it had to be centuries old. If walls could talk, that place would have some stories.

To the west of the compound lay PB Sandford, and to the southwest Alpha Xray. Everything to the south and east was bandit country. To one side of the compound was a concealed observation position (OP) — little more than a crater scraped in the hard dirt, with some camo-netting slung over it. It was large enough for the FST to crawl into, and keep eyes-on below.

Once we’d set up camp, I had a chat with the JTAC who’d stood in for me whilst I’d been away, a guy called Stu. He briefed me on what had been going on in the Triangle. I was itching to get the handover done with, and get back in the hot seat with ‘my lads’.

Stu talked me around a new bit of kit that he’d been using — a Rover terminal. It was the size of a small laptop, and it enabled the JTAC to see what the pilot was seeing, in real time. It fed off a live downlink from the pilot’s sniper optics, which beamed down the video images. He passed me the Rover terminal as part of the handover.

‘It’s a top piece of kit, mate,’ Stu reassured me.

‘Oh fuck aye,’ I told him. ‘If it does what you say, it’s mint.’

Stu talked me through my ASRs — I had air booked at first light and last light for the next three days. Those were proving to be the enemy’s favourite times to hit us. And that was pretty much it: handover done. Stu got a lift back to FOB Price with the resupply convoy that we’d come in on, and we were back in action.

I got my first chance to use the Rover terminal that evening, when I got a lone F-15, Dude One Five. I had him for an hour, and it left me in no doubt as to the value of that Rover screen. I gazed in to the blue-green glow, seeing everything the pilot saw as he viewed it, in up-close detail. As he talked me through the terrain, I was right there with him. It was an awesome bit of kit, and I couldn’t wait to see how it performed in a combat situation.

There was a well nearby, and that afternoon I’d washed all my kit. After doing the Op Loam convoy, and the journey in here, everything was minging. The well water came from a good twenty metres down, and for the split second that I chucked it over myself I was cool, in spite of the 46°C heat. I put my combats back on soaking wet, in an effort to keep the heat down.

Butsy was camping out with us at MOE, and he came over to have a quiet word at the well. The OC told me he was chuffed as nuts to have us back again. We weren’t from his regiment, but we’d become like his boys. It was good to have the A-Team back together again. We were B Company’s FST, and I was their JTAC.

That night I dossed down on my blow-up bedroll on the dirt floor. It was mid-summer, and there was no chance of rain. No one bothered with mozzie nets, although there was something that kept biting. I drifted off to sleep with the Afghan stars for company, and feeling pretty damn happy to be back where I belonged.

At 0430 the enemy hit us. Everyone was up at stand-to and ready to rumble. From out of nowhere, our position was raked with small arms fire. I heard the crack that high-velocity bullets make — a sound that had become so familiar over the last few weeks — as rounds went whining over the wall of the compound and slamming into the open desert beyond. At the same time I could hear PB Sandford getting smashed, so it was a two-pronged assault. I had an F-15, Dude One Three, overhead, but there was nothing to be seen. Via the Rover terminal downlink, I could appreciate the problem the pilot was facing. Wherever the enemy were hitting us from, they were well hidden in the dense bush of the Green Zone.

Once we’d beaten off the enemy attack, Sticky and I headed out to get a feel for the lie of the land. The compounds to either side of us were deserted, but in one we discovered these bulging hessian sacks. Inside each was a sticky, dark sugary substance — so-called ‘brown’ — the first step in refining opium poppy into heroin.

On the windowsill above the sacks was a string of Muslim prayer beads. It struck me as pretty rich the way the Talibs combined their hard-line version of Islam, and heroin. Somehow it was wrong to drink beer, but OK to bankroll a war via hard drugs. The contents of those sacks had to be worth a mint. We took the sacks, sliced them open with our bayonets, and emptied the contents into the river that ran past our position. I felt good doing it. That way, no one would be using that brown shit to buy bullets or bombs to mess up any of our lads.

A shura was in the offing. The OC wanted to explain to the local elders — blokes like the one whose compound we were camping out at — what we were doing here. As per usual we had Intel that the enemy would attack, just as soon as the shura was over.

I had a pair of A-10s and a pair of F-15s overhead. I cleared it with the OC that I’d get them to fly a low-level show of force over the meeting, then bank them up high so those at the shura were free to talk. I got all four aircraft in low and fast with flares, then banked them off flying air recces all around. It was an awesome show of force, and it must have put the wind up the enemy. Our team got in and out unmolested, but we had picked up some interesting enemy chatter. Commanders were ordering their men to stay in their ‘hidden positions, to avoid getting seen by the aircraft’. They were telling their men to await orders to attack and kill the ‘infidels’. I guess that was us, then.

The first, probing attack came at the enemy’s favoured time — first light. Overnight, a raging sandstorm had blown up to the south of us. I didn’t have any fast jets, for nothing was able to get airborne. All I had was a Predator Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) orbiting above. The MQ-1 Predator does carry one Hellfire missile under each of its glider-like wings, but it is basically designed for surveillance tasks. At eight metres long, it orbits at 20,000 feet, the propeller to the rear of the aircraft driving it along at a cruising speed of around 130 kilometres per hour. The UAV is invisible from the ground, and totally silent. As a stealthy spy-in-the-sky it was an awesome piece of kit, and it had a fantastic downlink to my Rover terminal. But a ground attack aircraft it was not.

At 0530 all hell broke loose down at Alpha Xray. First came the angry crackle of small arms fire, as the enemy opened up on our version of the Alamo. Then came the swoosh-boom of RPG rounds slammin

g into the base. An instant later the platoon were returning fire, with their 50-cal heavy machine guns chewing into the enemy positions. The thump-thump-thump of the big guns was interspersed with the noise of SA80s firing off on single shot, and the boom of grenades from the lads’ underslung launchers. The battle noise rose to a climax, as the platoon down at AX went apeshit trying to repel the attack.

The lads knew that I had no air, for I’d given an all-stations warning just as soon as I’d got word of the sandstorm. Via the Predator downlink I could see the enemy pouring in a barrage of fire on to AX. Tracer rounds and RPGs were streaking through the air and slamming into the sandbagged position on the compound roof. With the GeoCell map I could pinpoint exactly where the enemy were hitting us from: it was a position codenamed Golf Bravo Nine Two. If only I had some proper warplanes overhead, I could well and truly smash them. We needed some air power badly, for the platoon down at Alpha Xray looked in danger of being overrun.

I could feel my frustration levels boiling over. But just as quickly as the contact flared up, it died down to almost nothing. As it did so the enemy chatter started going wild.

‘We have tested their defences, brothers, and now we know where to hit them,’ a Commander Jamali was telling his men. ‘Remain in your hidden bunkers and trenches: await the order for the main attack. But if the infidels come out on foot, open fire and kill them.’

It looked as if that was just a skirmish, then. The big battle was still coming. I lost Overlord Nine Three — the Predator — which was out of flight time. With the sandstorm raging I had no more aircraft, and the airspace above the Triangle remained empty.

That airspace — my airspace — had the codename ROZ Suzy. ROZ Suzy covered a 7.5-nautical-mile square box of air encompassing Adin Zai, Rahim Kalay and all terrain in the Triangle. I had to declare ‘ROZ Suzy hot’ if it all went noisy, and ‘ROZ Suzy cold’ when the contact was over. Right now ROZ Suzy had gone cold, but it was anyone’s guess as to how long it would stay that way.

Fire Strike 7/9

Fire Strike 7/9